That Infidel Place

On 16 October 1869, the ‘College for Women’ opened at Benslow House in Hitchin, 30 miles south of Cambridge. This was a small-scale start in a rented property but the new College was born of an audacious vision. The goal was to create a permanent institution and in time to secure full membership of the University of Cambridge for the College and its students. This creation would shake the foundations of British higher education and have an impact across the world. As student numbers grew, and the Hitchin lease drew to an end, it was decided to move nearer to Cambridge for ease of integration into the life and work of the University. Various options were debated and in 1872 a site close to Girton village was secured. Here there was room for buildings and gardens and the potential for later growth.

The College for Women, Benslow House, Hitchin, circa 1869 (archive reference: GCPH 13/1/1)

The College for Women, Benslow House, Hitchin, circa 1869 (archive reference: GCPH 13/1/1)

The move to Cambridge

In October 1873, the College, and its then 13 students, moved from Hitchin to Girton into a building designed by Alfred Waterhouse (and later augmented by both his son and his grandson). The new building could accommodate up to 21 students and three resident staff. Its three floors also included a dining hall (now Old Hall) and kitchens, reading room, reception room, three lecture rooms, a prayer room, entrance hall, and servants’ quarters. From the very beginning, Girton opened a door to the residential educational experience that is the hallmark of collegiate Cambridge.

The first building at Girton, circa 1873. It shows the blank wall where the Stanley Library is later added, and the bay window of the Hall (now Old Hall) funded by Lady Stanley (archive reference: GCPH 3/1/5)

The first building at Girton, circa 1873. It shows the blank wall where the Stanley Library is later added, and the bay window of the Hall (now Old Hall) funded by Lady Stanley (archive reference: GCPH 3/1/5)

A crushing defeat

Girton’s foundational aim was to enable women to gain university degrees. Victory at Cambridge was hard-won, only coming in 1948. In 1880, the first Cambridge campaign on the question was sparked by the examination success of a Girton mathematician. Although it did not bring Cambridge degrees for women, they were granted official permission to sit Cambridge University examinations. In 1887, when a Girton classicist outshone all her male peers in Tripos examinations, a committee was formed to promote women’s access to Cambridge degrees, but the goal remained elusive. An iconic moment in the struggle came on 21 May 1897. After 18 months of campaigning, the members of the University voted by 1,707 to 661 to reject a proposal to allow women to receive degrees. The pictured effigy was hung during the demonstrations that accompanied the voting and the victors rioted through the night. It was more than 20 years before the issue was again formally considered in Cambridge, and half a century before the tide turned.

Effigy of a female student hanging from the window in the centre of Cambridge during the protests of 1897, taken by Messrs Stearn (archive reference: GCPH 9/1/4)

Effigy of a female student hanging from the window in the centre of Cambridge during the protests of 1897, taken by Messrs Stearn (archive reference: GCPH 9/1/4)

A triumph of hope

Despite the University’s refusal in 1897 to grant degrees to women, in 1899 Girton embarked on a major new phase of building. By 1902, the College had constructed one of the largest dining halls in the University (serviced by new, larger kitchens), at the time the only indoor swimming pool in a Cambridge College, and two new wings (Chapel and Woodlands) that added 49 sets of lecturers’ and students’ rooms. There was to be no turning back now.

The Dining Hall, looking towards High Table, circa 1902 (archive reference: GCPH 8/2/1)

The Dining Hall, looking towards High Table, circa 1902 (archive reference: GCPH 8/2/1)

A College at war

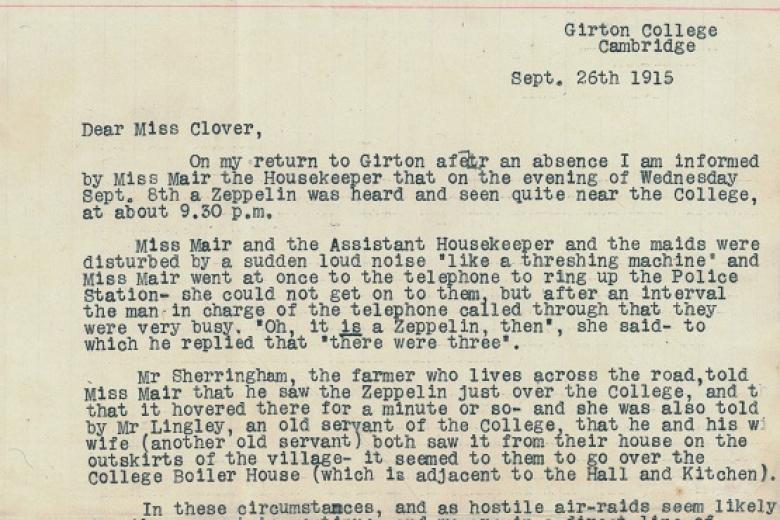

Girton has never been cut off from society. The First World War had a major impact on life at Girton just as it did across the country. The whole College lived with the constant fear of a telegram reporting a lost father or brother. Food and coal were rationed; several members of the academic staff were absent undertaking war work; vegetables and pigs were raised in the gardens. Girton students and alumnae contributed to the war effort in many ways. In particular, former and current students raised money to support the Newnham and Girton Unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, which cared for wounded soldiers close to the front. Many Girtonians undertook war work, including serving as doctors and nurses in Europe. The war also came close to home. In September 1915, a German zeppelin was seen over Girton, as reported in this letter from the Mistress to the College Council.

Letter from the Mistress concerning the sighting of a zeppelin, 26 September 1915 (archive reference: GCGB 2/1/21)

Letter from the Mistress concerning the sighting of a zeppelin, 26 September 1915 (archive reference: GCGB 2/1/21)

Votes for women

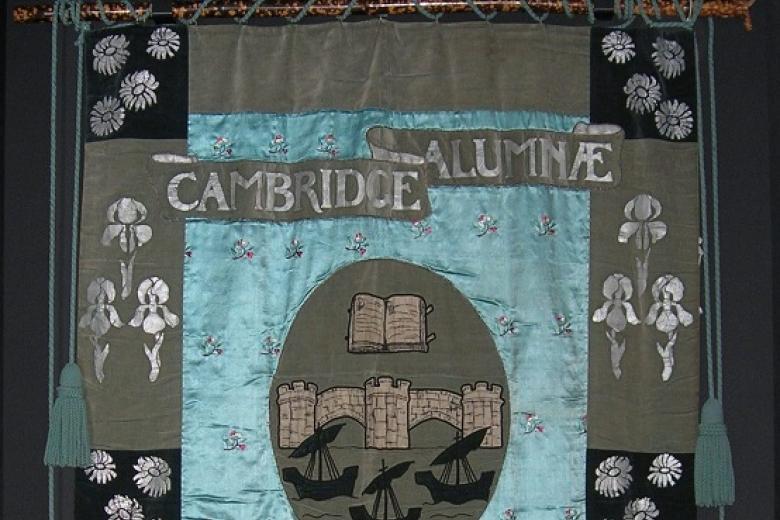

Girton has always been at the forefront of political and social movements designed to improve the position of women in society. Barbara Bodichon (1827–1891) and Emily Davies (1830–1921), leading founders of the College, were key figures in the mid-19th century campaign for women’s suffrage before stepping aside to concentrate on Girton. After 1900 the British suffrage campaign gained new momentum. Large suffrage societies, both constitutionalist and more militant, made suffragism a genuine mass movement. Suffrage societies were founded in Girton and Newnham, and together students from both Colleges designed and worked on the Cambridge Alumnae Banner, carried in a 1908 suffrage demonstration. In 1918 women over 30 gained the national vote (provided that they were on the local government electoral register or married to men who were). Aged 88, Emily Davies was one of those able to vote for the first time. In 1928 women finally won the vote on the same basis as men, but they were still not allowed to receive their degrees from the University of Cambridge.

Banner, made by students of Girton and Newnham Colleges, and carried at a women’s suffrage demonstration on 13 June 1908 (reproduced courtesy of Newnham College)

Banner, made by students of Girton and Newnham Colleges, and carried at a women’s suffrage demonstration on 13 June 1908 (reproduced courtesy of Newnham College)

Silver Jubilee

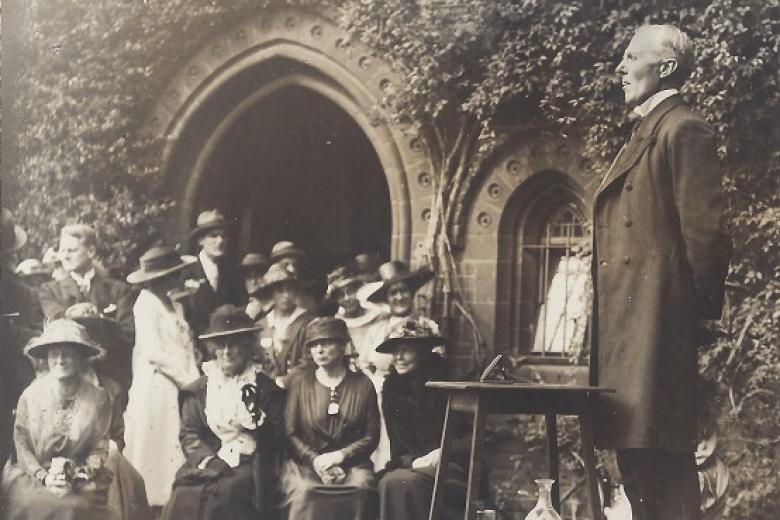

On the weekend of July 26 and 27 1919, Girton celebrated its Silver Jubilee. In the 50 years since its foundation the number of students in residence had grown from five to 166. Celebrations began with a garden party attended by around 900 people, including 326 former students. The guests were entertained by music from a band of the Grenadier Guards and heard speeches from the Mistress, Katharine Jex-Blake (1860–1951), the Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University, the Chairman of Girton’s Council and the eminent historian, Member of Parliament, and President of the Board of Education, Herbert Fisher (1865–1940), who planted a tree to commemorate the 50-year milestone. That evening, a celebratory dinner in Hall was accompanied by further speeches. Perhaps the most memorable words of the night were spoken by 78-year old Hitchin pioneer and suffragist, Louisa Lumsden (1840–1935). On Sunday, more than 200 friends and former students spent a further day in the College, many attending a special service in Girton Chapel.

Herbert Fisher, addressing the Silver Jubilee Garden Party, taken by Sport & General Press Agency Ltd, 1919 (archive reference: GCPH 12/3/1/7)

Herbert Fisher, addressing the Silver Jubilee Garden Party, taken by Sport & General Press Agency Ltd, 1919 (archive reference: GCPH 12/3/1/7)

Royal Charter

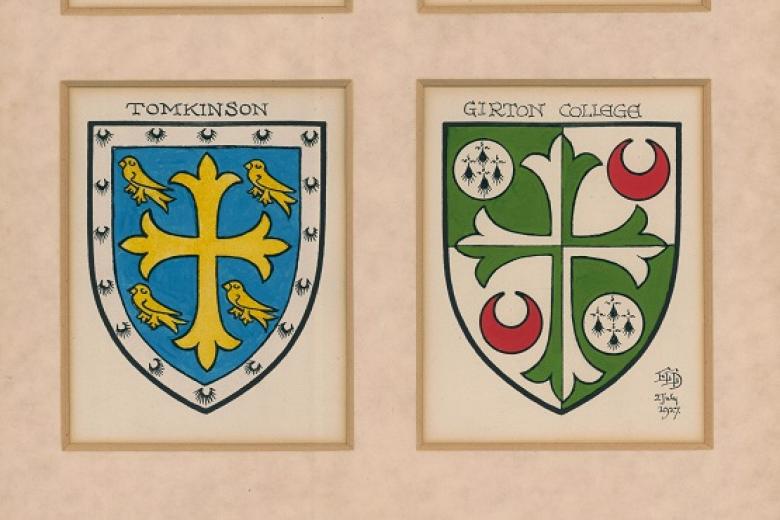

On 21 August 1924 Girton was granted a Royal Charter. To reflect its new governing structure, the College applied for a coat of arms, which was granted in 1928. The design was chosen to represent the family coats of arms of the key founders and benefactors of the College. Because Emily Davies’ family had no coat of arms, the green and white colours of the Girton design were chosen to reflect her Welsh ancestry. Barbara Bodichon is represented by the ermine roundels taken from her father’s family coat of arms (Smith). The cross dividing the shield into four is from the arms of Henry Tomkinson, while the red crescents are from the family arms of Henrietta, Lady Stanley of Alderley (Dillon).

The Girton key shields painted by Rev E E Dorling as used in the coat of arms designed by him, 1927 (archive reference: GCRF 6/1/26)

The Girton key shields painted by Rev E E Dorling as used in the coat of arms designed by him, 1927 (archive reference: GCRF 6/1/26)

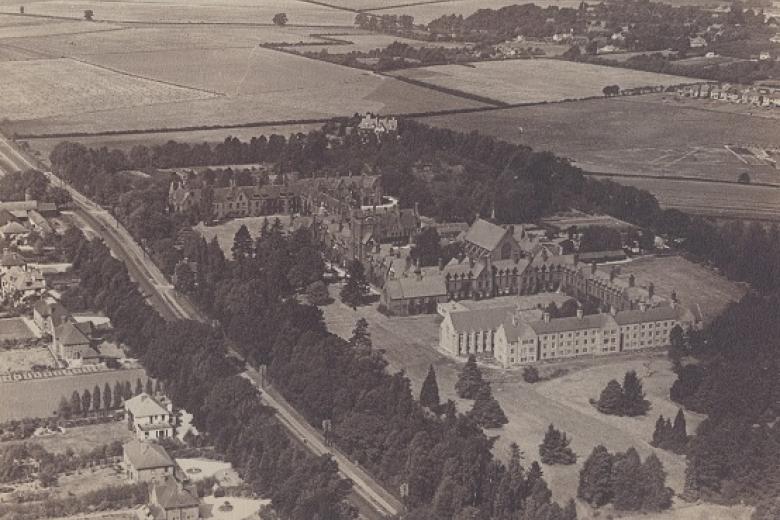

Expansion of the estate

In 1930 a new phase of expansion began in Girton – a signal of the College’s continuing confidence despite the University’s ongoing opposition to awarding degrees to women. Central to the project was a new and larger library, later named after its principal benefactor, Thomas McMorran (fl.1890s–1930s). This beautiful building, with its spectacular arched ceiling, continues to be the focal point of today’s library. The new College buildings also included New Wing, with additional accommodation for 27 students and four members of the resident staff, a soundproof music room, and the Fellows’ Dining and Drawing Rooms. It is fitting that today Girton’s library – one of the largest and most comprehensive College libraries in the University – houses the Girton Archive and Special Collections. These include material on the history of the College, and on its engagement with wider campaigns for women’s education, the suffrage movement and feminism.

Aerial view of the College, taken by Pan-Aero Pictures, 1933 (archive reference: GCPH 3/18/5)

Aerial view of the College, taken by Pan-Aero Pictures, 1933 (archive reference: GCPH 3/18/5)

Wartime Girton

In 1939, once again Girton prepared to operate under wartime conditions. Corridor windows were painted dark blue and blackout curtains were hung in student rooms. In time many Girtonians took a two-year degree under War Emergency Regulations, and a Red Cross detachment was formed in the College. Many students and Fellows postponed study and research to help the war effort, providing valuable work that spanned the civil service, military, medical and scientific appointments and counter-intelligence. For example, recent student and future Classics Fellow, Alison Duke (1915–2005), worked in Greece helping refugees, while Eva Hartree (1873–1947), a student in the 1890s and the first woman Mayor of Cambridge, helped support Jewish refugees in the city. One of the many bound by the Official Secrets Act, who rarely spoke of the war, was brilliant mathematician Mary Cartwright (1900-1998), Mistress of Girton from 1949 to 1968. Despite her important scientific contributions, above all to the effectiveness of radar, she modestly reported that her most useful war work had been packing parachutes for men sent into enemy territory.

Bletchley Park personnel, at work in the Hut 6 machine room in Block D, probably early 1945 (image reproduced courtesy of Bletchley Park)

Bletchley Park personnel, at work in the Hut 6 machine room in Block D, probably early 1945 (image reproduced courtesy of Bletchley Park)

Success! Degrees for women

On 21 October 1948 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the late Queen Mother (1900–2002), became the first woman to receive a degree from the University of Cambridge. The first students of Girton and Newnham graduated the following November. Both of these ceremonies were made possible through Cambridge University finally, and unanimously, voting to grant degrees to women on 6 December 1947. Although Girton’s foundation had helped to stimulate the national campaign for full equality of access to higher education, Cambridge was the last British University to grant them degrees. This important breakthrough is celebrated at the annual College Feast.

More reform lay ahead – for example it wasn’t until 1956 that women and men could take their examinations in the same room. In the meantime, Girton received a supplemental Royal Charter in 1954 which gave it the same form of government as the men’s Colleges. The next step would be progress towards other forms of widening participation at Cambridge.

The Queen Mother (Visitor 1948-2002) with four Girton Mistresses, from left Mary Warnock, Mary Cartwright, Juliet Campbell and Muriel Bradbrook.

The Queen Mother (Visitor 1948-2002) with four Girton Mistresses, from left Mary Warnock, Mary Cartwright, Juliet Campbell and Muriel Bradbrook.

A modern administration

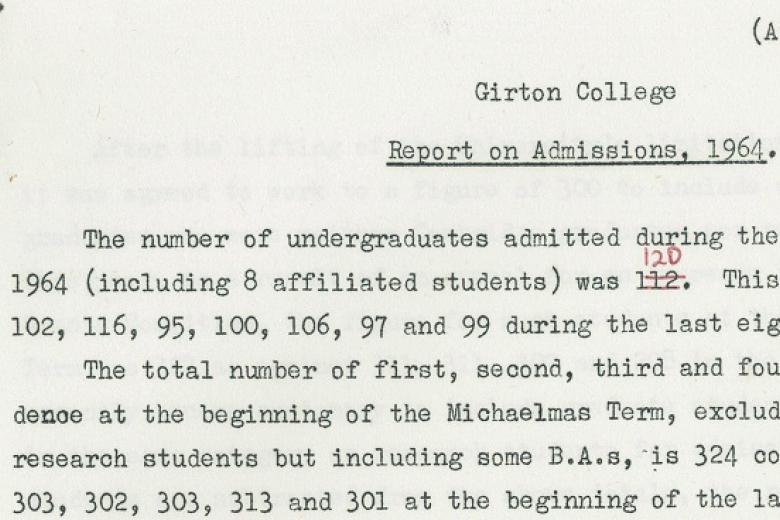

The Girton community relies upon the hard work of its administrators. In the early decades these were a small number of the resident staff – women like Gertrude Jackson (1858–1920), resident Junior Bursar from 1891 to 1898, and Mary Clover (1876–1965), devoted College Secretary from 1903 to 1933. From 1927 to 1964, resident Fellow Kathleen Peace (1904–1974), dealt ‘with practically everything administrative’, including admissions paperwork, from the hub of the Girton ‘College Office’.

1950 saw a key moment in the emergence of the modern administrative structure, when Marjorie Docking (1926–2013), already secretary to Kathleen Peace, became secretary to the Mistress and was asked to establish and run the first ‘Tutorial Office’. In 1964, Marjorie Docking went on to establish the separate Girton Admissions Office, which she ran until her retirement in March 1986. From these origins, the modern Girton administration, with its dedicated staff members, grew. 2004 would witness the unification of the Tutorial and Admissions offices under the leadership of Angela Stratford, who is still in post.

Extract from Marjorie Docking’s first report as the newly appointed Admissions Secretary, 1964 (archive reference: GCAC 1/1/1)

Extract from Marjorie Docking’s first report as the newly appointed Admissions Secretary, 1964 (archive reference: GCAC 1/1/1)

The first 100 years

After 100 years, Girton had achieved its foundational aims. It was a permanent institution, integral within the collegiate University, offering a full range of subjects and graduating over 100 women each year. There was much to celebrate and in 1969, 750 alumnae returned to do just that with current students, staff and Fellows and the Visitor, HRH The Queen Mother. The centenary was not, however, a time for complacency. It was rather a call to action. There would be a new round of expansion, a decision to move to co-residence and an enthusiasm to position the College at the leading edge of a new drive to widen participation.

Centenary Ball Poster

Centenary Ball Poster

Poised for expansion

One hundred years from its foundation, and with student numbers rising nationally, the time was ripe to begin a new phase in Girton’s history. In 1969, with help from a generous grant from the Wolfson Foundation, and the invaluable support of our alumnae, a three-acre site for a brand-new College building was acquired on Clarkson Road, close to Cambridge University Library and the central Faculties. Building work began in 1970, and by 1972 ‘Wolfson Court’ was open, offering 100 new undergraduate study-bedrooms, ten rooms for graduate students, several teaching rooms and a cafeteria that quickly became popular with students and staff, residents and non-residents alike.

In June 1972, Lord Wolfson of Marylebone attended the official opening ceremony and unveiled a plaque to mark the occasion. That year, about one-quarter of Girton undergraduates lived in the new building. In the 1970s, universities across the UK were expanding: Girton too was ready to grow.

Lord Wolfson of Marylebone opens Wolfson Court, 12 June 1972 (photo: Cambridge News)

Lord Wolfson of Marylebone opens Wolfson Court, 12 June 1972 (photo: Cambridge News)

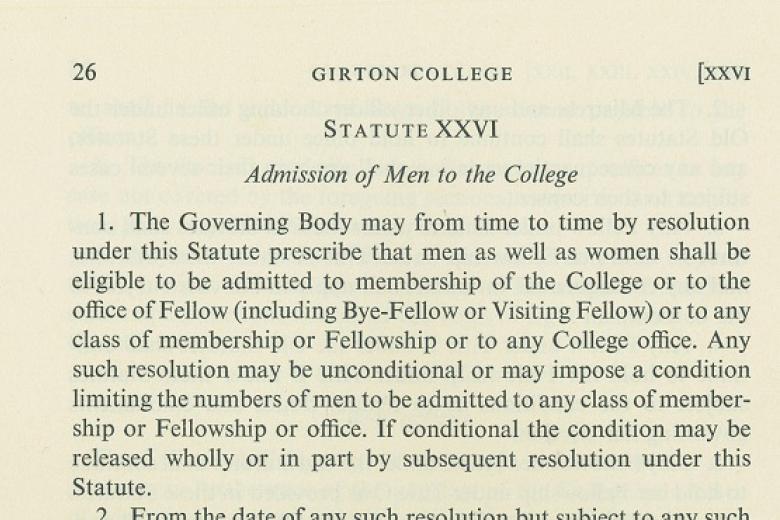

Going mixed

The late 1960s and 1970s brought great change in universities in Britain and across the globe as well as increasing debate in single-sex institutions about co-residence. In 1969, under the clear-eyed guidance of the new Mistress, Muriel Bradbrook, the College began the process of amending its Charter and Statutes to allow a future vote to admit men, an amendment that was in place by 1971.

Five years later, in 1976, the vote was taken: Girton became the first of the women’s Colleges at Cambridge and Oxford to embrace co-residence. The Fellowship changed first, with men admitted in 1977.

The first male graduate students arrived in October 1978 and the first 58 male undergraduates in 1979. Co-residence was a great success. By 1983, there was a gender balance at the undergraduate level in the College – something that continues today (and without quotas). Although there is no statutory requirement, Girton’s current Senior Officers are all women, and the Head of House – uniquely in Oxford and Cambridge titled ‘Mistress’ – has never been a man.

Statute XXVI Admission of Men to the College (archive reference: GCGB 1/2/2 pt)

Statute XXVI Admission of Men to the College (archive reference: GCGB 1/2/2 pt)

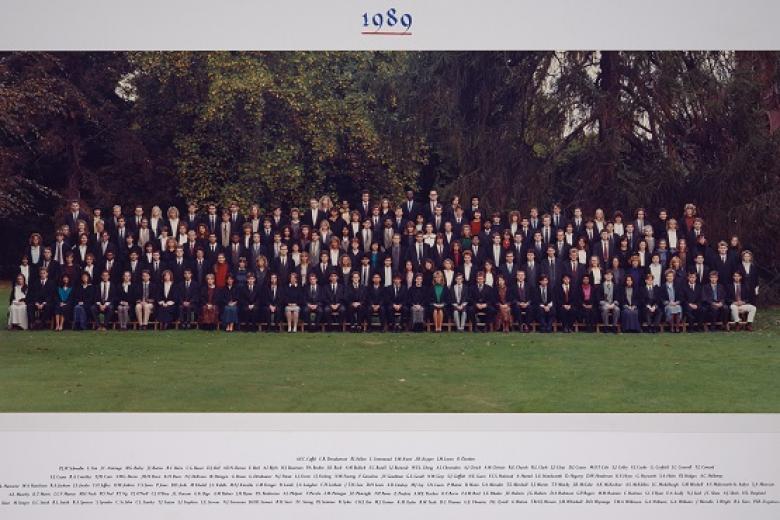

Mass expansion of Higher Education

The early 1960s saw growing demands for British higher education to expand to admit more students. The Robbins Report of 1963 (Committee on Higher Education, 1963) supported this aim, and called for university places to be made available to all ‘qualified by ability and attainment to pursue them and who wish to do so’.

The 1960’s and 1970’s saw a gradual increase in numbers attending higher education institutions from less than 5% to around 12% of 18 year olds. There were no student loans, fees were paid by local education authorities, and a means-tested annual grant helped cover living costs.

In 1989, Kenneth Baker, Conservative Secretary of State for Education, called for a further increase in student numbers, leading to a rapid rise between 1988 and 1992. By 1992, participation had reached 30% of school-leavers.

In 1998, tuition fees were introduced for most British students. This presaged the introduction of student loans. Subsequent increases in tuition fees have brought an average debt today of £50,000 for an English graduating student, or one from Scotland attending university south of the border.

1989 Matriculation photograph (Archive reference: GCPH11-4a-36-134)

1989 Matriculation photograph (Archive reference: GCPH11-4a-36-134)

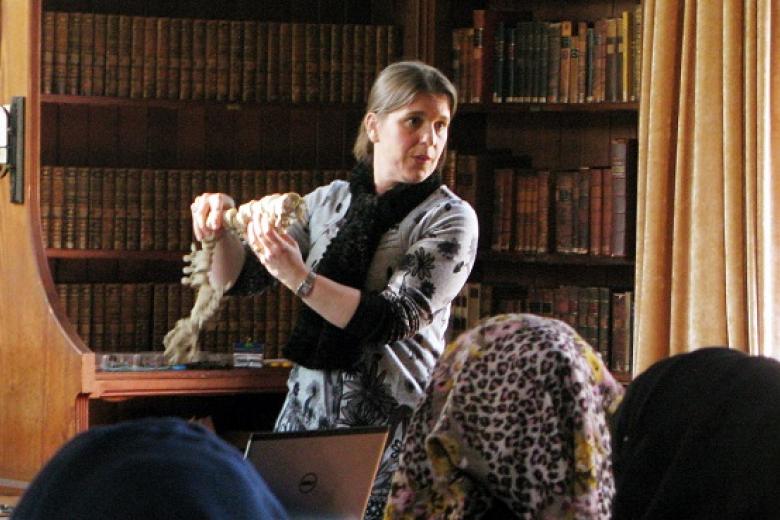

Widening participation

Significant changes in recent years have fundamentally affected access to higher education. Student funding arrangements have altered dramatically and student demographics are changing. However, one constant in this ever changing landscape is Girton’s commitment to widening participation. Nearly 70% of Girton’s home student intake is from the state school and maintained sector.

A key element of this commitment is our extensive outreach programme for schools which has twin aims:

- to encourage applications both to the College and to the University from students with high academic ability, enthusiasm and potential.

- to raise the aspirations of students as they consider their futures and to help remove perceived barriers to considering applying to Cambridge, and university in general.

Girton is linked with the UK locations of Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull and Wolverhampton in the West Midlands, and with Camden in London where we run various events – masterclasses, taster days, visits, presentations – for students from Year 7 upwards as well as for parents, supporters and teachers.

Dr Sarah Fawcett leading the Medicine masterclass in the Stanley Library, 2014

Dr Sarah Fawcett leading the Medicine masterclass in the Stanley Library, 2014

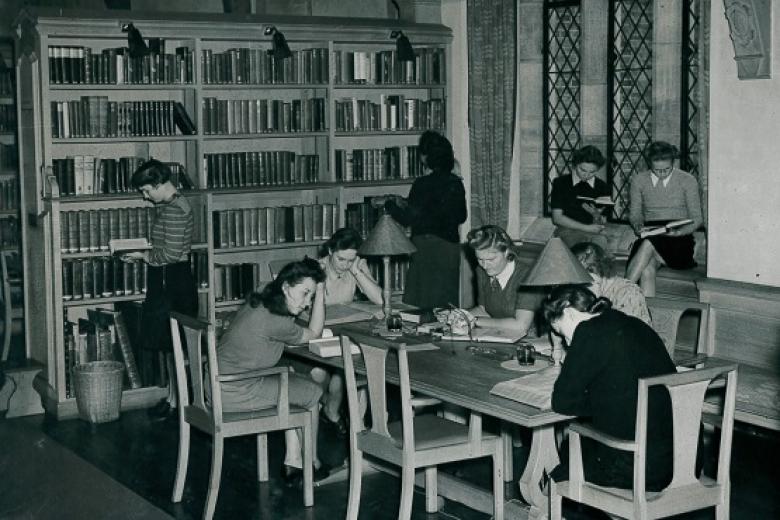

Duke Building (Library and Archive Centre)

Girton has one of the largest College libraries in the University holding in the region of 95,000 books. The 1930s McMorran Library, with its awe-inspiring vaulted timber ceiling, was complemented in 2005 by a multi-award winning extension, the Duke Building.

Named after Alison Duke (1915–2005) (Classics,1934), Director of Studies in Classics and Senior Tutor, this new building created a spacious IT resource area and a state-of-the-art repository to house the Archive and the Special Collections.

These collections range from rare Sanskrit manuscripts to gifts of books from Girton’s most notable early supporters such as Tennyson, Ruskin and George Eliot. They also include internationally important collections on the history of women and work, the suffrage movement, women’s education, and Girton’s ground-breaking history.

Student studying in the McMorran Library

Student studying in the McMorran Library

Excellent on-site sporting facilities

The College values sport for women and men. Students from diverse backgrounds learn to work together in teams developing leadership skills or compete individually to expand talents and abilities that complement their studies. All learn the value of a work-life balance.

1,060 Girton students have played for the Blues – Oxford versus Cambridge first team games – across 46 different sports, and in 2016 the College hosted its first University Blues cricket match, making use of the first-class facilities of Girton grounds and the John Marks Sports Pavilion.

Other new facilities include the Grassie squash court, the refurbished indoor swimming pool and the multi-gym and ergo room, which were officially opened in 2013.

Excellent on-site sports facilities include a multi-gym popular with the whole College community, 2017

Excellent on-site sports facilities include a multi-gym popular with the whole College community, 2017

Award-winning new wing

In October 2013, the College opened an award-winning new wing for accommodation to enclose Ash Court, the largest expansion of its buildings in 40 years, overlooking the courtyard, pond and orchard.

The three-storey building provides 50 en-suite study bedrooms, all of which are wheelchair accessible, as it houses a life to all floors. It also includes six rooms which are specially adapted for disabled users, six kitchens, a laundry and leisure hub.

It is one of the most energy-efficient student accommodation buildings in the UK, providing half of its on-site energy requirements from renewable sources including roof-top photovoltaic panels.

Ash Court, 2013

Ash Court, 2013

Estate masterplan

In October 2016, Girton was granted outline planning permission to realise an ambitious masterplan for its historic main site. After three years working closely with planning officers in South Cambridgeshire District Council, Historic England, every College constituency and representatives of the local community, Girton’s multi-disciplinary team of consultants devised a visionary proposal which all parties could endorse. Appropriately for our location in the Green Belt, the plan preserves the heritage and amenity value of the site, while opening up a host of new possibilities for the future of the estate.

The outline plan could, for example, accommodate a substantial expansion of student numbers, particularly postgraduates; it would support the consolidation of the College onto a single integrated site; it contains an option for enhanced conference facilities and it offers innovations in layout and circulation.

Most importantly, there is now a firm foundation from which to plan for the long run, with enough flexibility to meet the evolving needs of students and staff in a competitive and uncertain world.

Estate Masterplan showing new areas for future development

Estate Masterplan showing new areas for future development

Strategic vision

“Promoting excellence in diversity is at the heart of Girton’s strategic plan. The principle of inclusion is a foundational aim; our reputation for excellence is integral to the international standing of Cambridge University. As a residential educational venture Girton prizes environmental sustainability in life as well as at work; as a permanent institution, we have taken bold steps to underpin the endowment. As our ambitious seven-year plan draws to a close, Girton is ready to embrace and shape the future. We shall, in the coming years, continue to offer a leading edge learning experience spanning almost every university subject, enriched by success in widening participation and underpinned by an ethic of care.” - Professor Susan J. Smith, Mistress (2009 – 2022)

The College Visitor, Lady Hale and The Mistress, Professor Susan J. Smith, unveiling the new blue plaque (2019)

The College Visitor, Lady Hale and The Mistress, Professor Susan J. Smith, unveiling the new blue plaque (2019)