Facts and Findings: Girton’s Working Group 2020-22

Published: May 2023

It was the University of Cambridge’s student population who in effect carried the vision of the Vice-Chancellor’s Legacy of Enslavement Inquiry into the colleges. No sooner was the Vice-Chancellor’s Advisory Group established in 2019, than an independent student-led initiative followed, among other things stimulating colleges to take up their own inquiries. In Girton this found a ready response, not least from the Mistress. By the time that the College Council’s legacies of enslavement planning was more than a gleam in the eye, Girton’s students -- undergraduates and postgraduates -- were coordinating with senior members to make their own College-wide response to the Black Lives Matter incidents of 2020. This was under the banner of 'Girton against racism'. It was a sign of the seriousness with which College had to face one of the lasting legacies of eighteenth and nineteenth-century enslavement, the racist dimensions of inequality in present-day society. Girton set up a Legacies of Enslavement Working Group (LEWG) of Senior Officers and Fellows, along with an alumnus, in Michaelmas Term 2020.

A scoping exercise

As a starting point, the College Council asked LEWG to enquire into those aspects of College’s history and endowments that might have had links to the Atlantic trade in enslaved people and other historical forms of coerced or indentured labour. LEWG interpreted the request by undertaking a scoping exercise; at its heart was a one-year programme of part-time research, reflection and writing. It reported back to Council in Easter Term 2022. The Group understood its mandate as a matter of institutional self-knowledge as well as affording particular recognition to those whose labour was extracted under intolerable circumstances. It also understood that enslavement stands out among exploitative practices for its negation of legal personhood. This is what made it possible for enslaved persons to be treated as property, and is what makes recognition such a significant response.

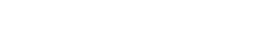

Two volumes of minutes of ‘Girton College’, the first governing body (archive reference: GCGB 4/1/1 and 4/1/2). The open volume shows the minutes of a meeting held on 22 July 1872. These minutes formed one of the sources used in the research.

The Working Group prioritised an examination of endowments and donations of a monetary kind. It undertook a precautionary audit of diverse College holdings and collections to see if there were any objects -- such as furnishings or art works – that might be directly derived from enslaved labour.

The Stanley Library, April 2023 (archive reference: GCPH 2/5/22). The Stanley Library houses part of the College’s collections, which include books, furniture, clocks, rugs, paintings, and sculptures.

The Group's priorities were guided by the historical period in question and thus by certain presumptions concerning women’s activities in the mid-nineteenth century. Within Cambridge, Girton was in a position it shared only with Newnham to focus on the role that women’s prime source of independent wealth, inheritance, played in the development of women’s higher education. It is here that the Group expected to find proceeds from enslavement, and here too find contemporary debates on slavery and its abolition among educationalists and others around the time of College’s foundation.

While work could be carried out in the Girton College Archive, under pandemic restrictions archival visits elsewhere were necessarily curtailed; instead, use was made of holdings searchable online and of documents located elsewhere that could be copied on request.

Investigation focused on two areas:

First, a narrow but detailed enquiry was undertaken into the sources of the wealth that came to College from those most prominent among Girton’s early founders, benefactors and supporters. Following an original four very well-known names in Girton’s history, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Jane Catherine Gamble and Henrietta Maria, Lady Stanley, the Group added two who were also early students, Katharine Jex-Blake and Gwendolen Crewdson. Its search in each case was for any traceable link to obvious proceeds from enslavement included in their contributions.

Left: Katharine Jex-Blake, taken by C Vandyk, circa 1916 (archive reference: GCPH 5/8/1). Katharine Jex-Blake (1860–1951) was a student at Girton 1879–1883, Resident Lecturer in Classics 1885–1901, Vice Mistress 1903–1916, Mistress 1916–1922.

Right: Gwendolen Crewdson standing in front of the original College entrance taken by Dorothy Marshall, 1905 (archive reference: GCPH 10/24/22). Gwendolen Crewdson (1872–1913) was a student at Girton 1894–1898, College Librarian and Registrar 1900–1902, Junior Bursar 1902–1905. Dorothy Marshall (1868–1966) was Girton Resident Lecturer in Chemistry 1897–1906.

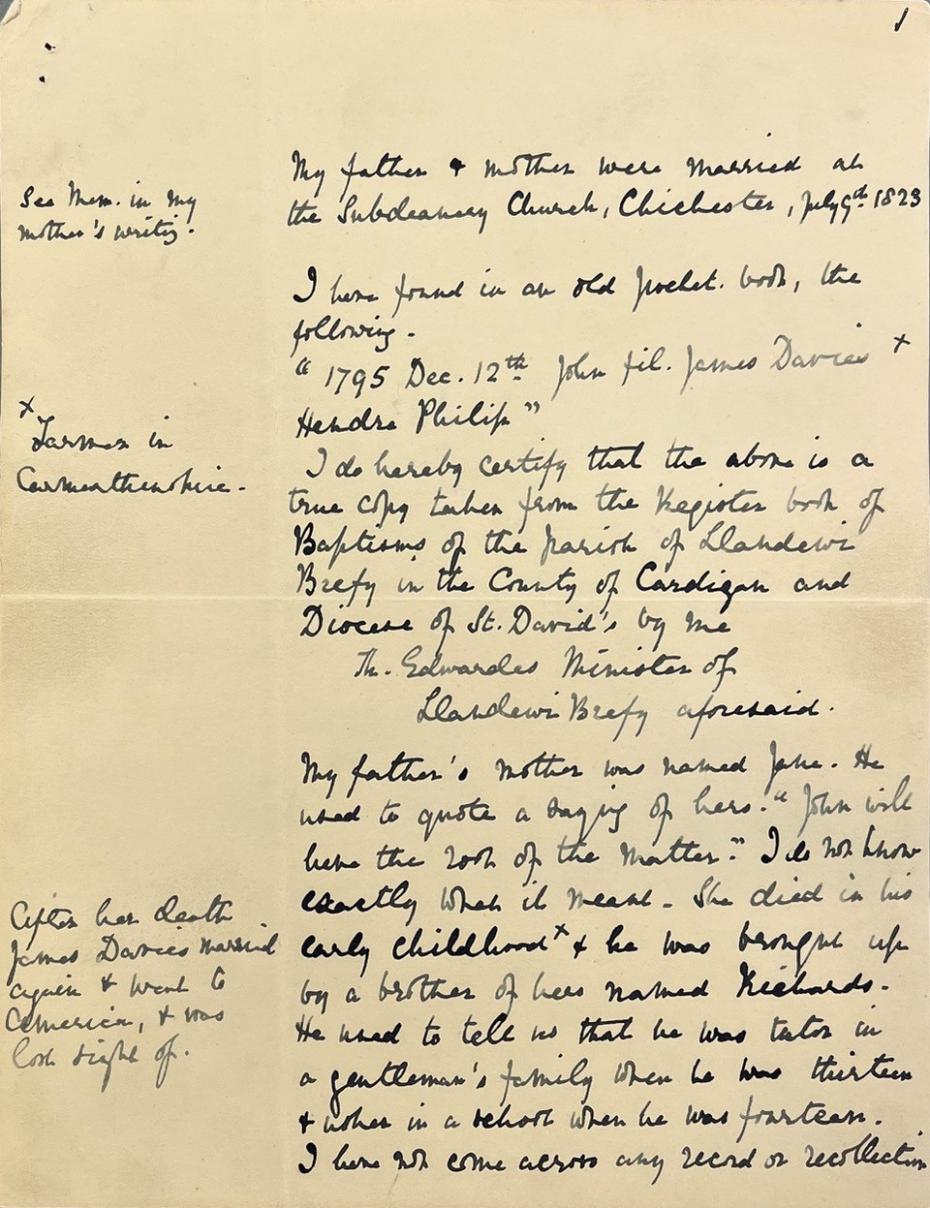

Second, a wider survey was carried out with respect to a total of 69 individually identified benefactions (including from four of the above), which contributed to Girton’s flourishing over the period 1869-1929. These were all the gifts and bequests of £100 or over that went specifically towards establishing Scholarships, Prizes, Studentships and Fellowships. Several of these were named, whether in honour of a third party or after the donor. Defining a set of substantial endowments in this way would give at least some sense of a likely overall proportion of monies emanating from the enslaved labour of concern to College.

Notable findings

Girton College came into being through intensive but slow to materialise fund-raising efforts led by Emily Davies. Four of the six figures in our study either belonged to her circle of acquaintances and supporters or were students and then members of the College staff. Separate from these was a benefactor, who -- long before she left her legacy -- had once visited Cambridge but as far as we know had no ties with those involved in the campaign for a ‘college for women’. Her bequest came out of the blue in 1885, and was the most munificent that Girton had received by that point in its history. It has now acquired new dimensions. Neither Gamble nor Girton ever concealed the family links that made her an heiress of wealth generated by interests that ran on workforces of enslaved persons. But, until LEWG began its inquiry, these links had not been openly acknowledged either. She is the subject of the first Girton Reflects.

First page of ‘The Family Chronicle’, an account of family and other matters written by Emily Davies in 1905 (archive reference: GCPP Davies 1/1). This source tells us that Emily Davies' grandfather was a farmer in Carmarthenshire.

What of the other five figures, including Emily Davies? None had the same order of direct connection to enslavement following the Atlantic trade, but evidence of the extent to which the proceeds from enslaved labour touched their fortunes in such a way as to benefit College had to be investigated. The variation was considerable -- from no direct connection to suspected or demonstrable activities in an ancestral past. This is the subject to be taken up in detail in the next article of the Girton Reflects series.

Henrietta, Lady Stanley, with Lady Carlisle and Lady Mary Howard, taken by an unknown photographer, not dated (archive reference: GCPH 4/1/4). Henrietta, Lady Stanley (1807–1895) had 10 children. One daughter, Rosalind, later the Countess of Carlisle (1845–1921) would in time also be a major Girton donor and supporter. Lady Mary Howard (1865–1956) was one of Rosalind’s daughters.

The more the Group learned about the impact of resources derived from enslavement on the prosperity and development of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Britain, the more it began to appreciate the nexus between such wealth and the endowment of new educational institutions. Apropos the set of 69 gifts and bequests for scholarships and prizes of £100 or more, some 15 have been identified as possible candidates for research on significant connections. Including Gamble, in whose name College created a prize, the proportion is about 23%. That said, this is only an approximation until that research can be undertaken. The Group’s work has also given College new information on early funding more generally, and investigation is currently underway to gain a comprehensive picture of all of the 800 or so individuals whose donations – large and small – had come to College by 1900.

Part of a subscription list, 1882 (archive reference: GCAR 4/1/5pt). Lists such as this were an important source for the research.

Notable among Girton’s early supporters were those who made public their own views on enslavement, and the explicit similarities drawn between abolitionist rhetoric and arguments for women’s higher education will be a subject for later in this series. Overall, we should not be surprised if people subscribed to a spectrum of positions, which might or might not reflect knowledge about where their wealth had come from or the range of social circles in which they moved.

The Working Group became acutely aware of the disparity between specific flows of funding through the fortunes of named persons and the generally anonymous conditions under which their wealth was generated. To a limited degree, some of the anonymity can be lifted. From contemporary documentation concerning one of the nineteenth-century Virginian plantations that has become part of Girton’s history, a few of the 40 or so persons enslaved there (in the first half of the nineteenth century) are now visible as named individuals.

Recommendations

Recognition, and the acknowledgement that would bring, was key to LEWG’s recommendations. And this could only make sense as an ongoing process. Changing cohorts of students, generations of College alumni, anyone interested in education: what was done first for ourselves, as student representatives from the JCR and MCR reminded us, would also need to be open to engagement in several registers and with respect to ever-evolving interests.

One way of making recognition visible would be by giving it institutional form. This would acknowledge that it was in its growth as an institution that Girton benefited from enslavement practices.

Establishing a research hub to enlarge understanding of the College’s history could open up several avenues: creating a resource for ongoing study, inviting new ventures, and attracting interns, student projects and visiting scholars alike. Expanding thus on the limited work already undertaken would also be keeping its impetus alive.

Commemorative practices frequently proceed through identifying individuals by name. The LEWG recommended that Council encourage investigation into new sources of names. These might be relevant, for example, in the naming of a new Fellowship or postgraduate scholarship, or an undergraduate or Master's prize, some of which might also be directed towards work on understanding the conditions of enslavement, including its modern forms.

At the same time, the Working Group specifically recommended against deleting names from any present memorial. It has not yet been decided what form of supplementary information might be needed in certain cases.

Apropos the Gamble legacy, the Group suggested that College might think of a new memorial (perhaps a public sculpture or some such, within the buildings or grounds), which would stand for a generalised recognition of those whose work created some of the wealth that came to Girton.

Over particular issues to do with the university and college experience of BAME students, especially undergraduate or Master's students, it is recognized how much their environs at Girton matters.

LEWG’s main recommendation was that College should set up dedicated bursary support, and it is hoped that conversations would continue about other initiatives, such as corridor art.

The Working Group's recommendations have been adopted by the College through its Council. This included establishing the Legacies of Enslavement Committee to monitor the uptake of these various proposals. That there are costs here is acknowledged in explicit recognition of what has been to Girton's benefit.

Reflection

Three issues linger:

First was the need to confront the originating circumstances of the inquiry, a system of enforced labour (quite legal in the British colonies until formal abolition) that inflicted egregious suffering; this was not to be hidden from sight.

Second, parallels could be drawn between the kinds of issues with which those associated with Girton’s early years tussled and some of the conflicts that beset us today; this history speaks to the here and now.

Third, the Legacies of Enslavement Working Group was set up for a limited purpose, to establish that there was a case for inquiry; its research was thus circumscribed. Its fervent hope that its investigations would be seen as no more than work in progress has been endorsed by College.

While some of the Working Group’s activities will continue under the auspices of the new Committee, and will be taken into new arenas, the Committee also looks forward to fresh ways in which a future College and incoming generations of students and Fellows will decide what is important here.

Written by Legacies of Enslavement Committee (dated: May 2023)

Coming next: No.3, June 2023

A spectrum of connections.

The spectrum of involvement with and disengagement from enslavement interests on the part of five prominent benefactors and supporters.