At 3pm on 8 May 1945, Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced that war in Europe had come to an end. Today marks 75 years since VE Day. World War 2 had ravaged continental Europe and beyond and not a corner of British life was left unaffected.

At Girton corridor windows were painted dark blue and blackout curtains were hung in student rooms. The grounds were turned over for the growing of vegetables and for keeping pigs. The College worked hard to become self-sufficient in vegetables and students volunteered both in the gardens and in the kitchens. Crops included onions, carrots, lettuce, cauliflower, celery and tomatoes, and vast numbers of potatoes, over 19 tons in 1941–1942.

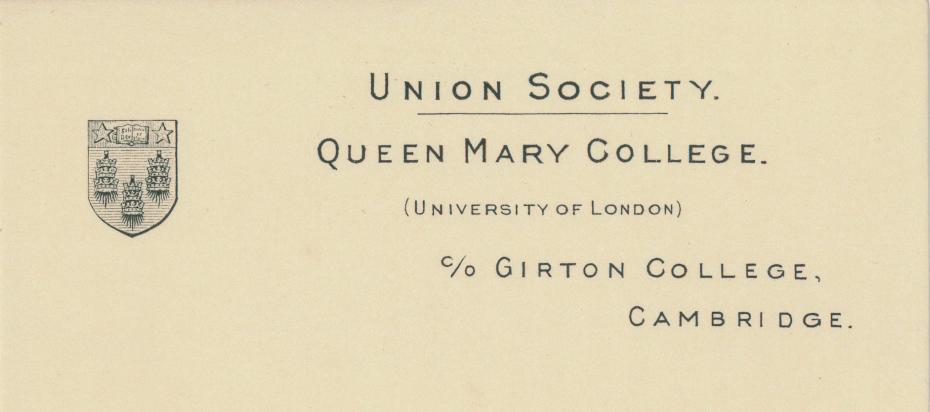

During the war the College welcomed new residents who were either escaping danger or working for the war effort. In 1939–1940, Girton gave a new home to 56 women students and two staff evacuated from Queen Mary College in London until they found more spacious accommodation in Cambridge. In 1939 the Girton College Refugee Fund was established, which would help three Czech and German student refugees to attend College. It also supported the war-time residence of Dr Elsbeth Jaffé (1889–1971), a scholar from Germany. The Grange was occupied by the army during some of these years, and from 1943 Girton also provided a home for a small number of women of the Voluntary Aid Detachment [VADs].